Monitoring: Ukrainian Crisis in Mass Media in Belarus

At the background of the Russian-Ukrainian informational war, Belarusian mass media look almost decent: they do not disseminate intentionally false information. However, sometime they openly express approvals or antipathies, and mix up facts and opinions.

For half a year of the Majdan in Kyiv, neutral publications about Ukraine prevailed in most state-run and independent mass media. State mass media usually avoided mentioning the actions of protests in the Ukrainian capital, but did not ignore the issue totally. Independent newspapers had much more publications on this topic; as a rule, they recounted the chronology of events and very seldom made any generalizations.

The war for the Crimea has evoked pro-Russian forces in the state propaganda machine, these forces have become more conspicuous on TV; but official persons, and alongside the state news agency BelTA have tried to keep neutrality.

Favors that are hard to conceal

Earlier research shows that the Belarusian press demonstrates obvious disproportion in covering foreign affairs: in our media, coverage of situation in Russia prevails. As for publications concerning other neighboring countries, they are more rare and usually republished from Russian media.

Belarusian mass media hardly have any special correspondents beyond Belarus, they do not have means to buy news feeds from foreign informational agencies or to send its journalists on business trips abroad. So, as a rule, exclusive materials about foreign life usually get to Belarusian media with a convenient opportunity: when a journalist travels as a tourist at his own expense or when a journalist takes part in an educational trip financed by receiving parties.

The Maidan in Kyiv induced and encouraged several Belarusian editorial offices to search for ways to get exclusive news. BelaPAN found an active blogger-photographer in the needed place; TUT.by sent its own special correspondent and used content of social media. Some Belarusian professional journalists went on a business trip to Kyiv either with the help of their editorial offices (it was afforded by projects based outside Belarus, like Euroradio, Radio Svaboda, Belsat, and the governmental newspaper Respublica), or at their own expense (Dzmitry Halko, Novy Chas newspaper). Besides, there were quite many volunteers from Belarus, and some of them ran personal blogs or author's columns in online media (Darja Katkouskaya, Andrey Strizhak). As a result, the information flow was wide, but not deep, since the authors did not have a possibility to immerse in the context and wrote in fact about real-time events. Verification of facts, getting confirmations from several not inter-linked sources were often substituted by links to Ukrainian or Russian mass media. Yet in coverage of the first steps of the new Ukrainian power which established after Victor Yanukovich's runaway to Russia, Belarusian media manifested lack of any systemic approach, any understanding of the Ukrainian “political kitchen”. But when Russian and Ukrainian media, including TV channels and informational agencies, set to full-scale informational war, Belarusian media sometimes fell its victims – they republished untrue information. The situation got complicated also by the fact that there were no Belarusian journalists in the Crimea, for example, in Donetsk.

It should be noted that informational agencies tried to abstain from putting on labels and spreading unverified news. Meantime, the state agency BelTA didn't “notice” attempts of the Belarusian civil society to express solidarity with Ukraine, while for the private agency BelaPAN information about it has become a kind of trademark and source of exclusive content on Ukrainian issues, an attempt to link the issue with Belarus.

From March 28 till March 19 BelTA made 125 publication on the Ukrainian events, whereas BelaPAN hasd 186 publications. Analysis of publications of both the agencies proves the impression of prevailing neutrality in the materials. It is interesting to compare the number of biased publications which can be roughly called pro-Russian (Ru) and pro-Ukrainian (Ua), and also their appearance in chronology.

When comparing the two diagrams, we can see that BelTA hardly has any pro-Ukrainian publications, but pro-Russian are obvious, (image 1), whereas BelaPAN almost does not have any pro-Russian materials, and pro-Ukrainian articles appear sparsely (image 2). The percentage comparison looks more vivid: in the reporting period, BelTA had 30.4% of publications shown from the Russian standing and 4% — from Ukrainian. At the same time, BelaPAN had 6.9% of pro-Russia publications and 13.4% of pro-Ukraine. In the latter case, these were Belarusian politicians and civil activists who gave assessment of the events, criticized Russia's actions and expressed solidarity with the Ukrainians.

Such results might account for different sources of borrowing content as well as different requirements to publishing materials. BelaPAN, when describing the conflict in the Crimea, at least states that there are different sides and briefly retells the events. BelTA did not mention that the change of power in the Crimea and arrangement of the referendum to join Russia took place only after the peninsula was seized by armed people identified by Ukrainian government as militarized; still, a number of publications were balanced by the mentioning that the Crimean referendum was viewed by Kyiv as unlawful.

Frequency analysis of all publications of BelTA and BelaPAN within the reporting period shows that top 10 words of both agencies are almost the same.

It should be noted that both agencies had very similar correlation in frequency of mentioning the words “Ukraine”, “Crimea” and “Russia”, and also “Belarus”.

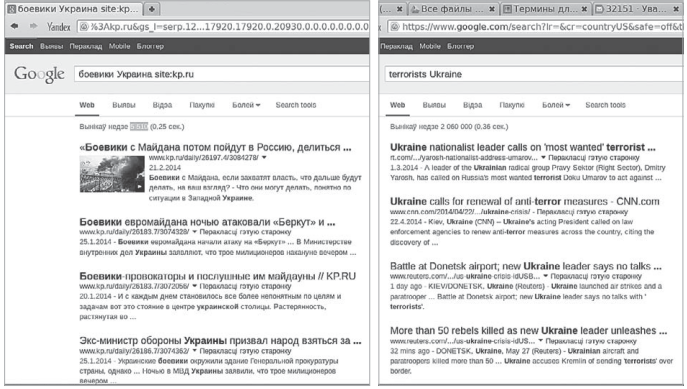

Terrorist or militiaman?

In the reporting period, Belarusian government avoided giving distinct assessment of the events in Ukraine and the Crimea, however since March 16 BelTA has started to recount events largely from the Russian point of view. And in analytical and discussion TV programs most participants supported the Russian positions in assessing the Crimea annexation. By that moment, Belarusian state TV (and there is no any other TV in the country) had mostly observed neutrality.

The “degree” of covering Ukraine in different media can be measured with words used to name the illegal armed groups.

The research used Google Advanced Search tool to evaluate tendencies, though does not provide a serious standing with concrete figures. A glossary was compiled in English, Belarusian, German, Russian, and Ukrainian (see the chart).

The research encompassed all websites in Belarus, Germany, Russia, the USA and Ukraine within a year, and also websites of specified media (ap.org, belapan.by, belmarket.by, belta.by, cnn.com, dw.de, euroradio.fm, faz.net, foxnews.com, naviny.by, nn.by, novychas.info, nv-online.info, onliner.by, pravda.com.ua, reuters.com, rt.com, sb.by, spiegel.de, stern.de, tut.by, tvr.by, ukrinform.ua, unian.ua, zviazda.by). It was curious to find out whether a news outlet used one and the same naming for the illegal armed groups in Ukraine and other countries, and whether it used euphemisms.

The black color in the chart shows the most frequent word or phrase, the light-grey color refers to the second frequent word.

As it turned out “paramilitaries” were used in the mass media to quote diplomats; journalists and editors themselves used other words. Only Russian media used different phrases to name the armed people confronting with the law enforcement agencies: there were “militia fighters” in Donetsk and Luhansk (39–40%), whereas “gunmen” referred to “gunmen of Majdan” and “gunmen of the Right Sector”.

The English language media called all the armed people confronting with the order “gunmen” as a rule, regardless of their venue of actions (40%), and if the confrontation crossed a certain line, the term “terrorists” was used (39%).

The picture was smudged by the Russian TV channel Russia Today which used the term “fighter” to describe respective persons in the same actions, whereas “terrorists” referred exclusively to the Right Sector representatives.

German language media placed emphasis on political preferences of the illegal armed groups of Donetsk and Luhansk — «Prorussische Separatisten» (26,6%), and the word “Bewaffnete” (gunmen, 26,5%) has become in fact a synonym. Curiously enough, the following close term in the line is “Terroristen” (24,7%) and «Kämpfer» (fighter, 21%).

In Ukrainian media (both in Ukrainian and in Russian languages), word frequency of these terms coincide with that of English language media: «бойовики» (gunmen, 55,6%) and «терористі» (terrorists, 3%).

Belarusian media revealed differences in the use of the terminology depending on the language used (Belarusian or Russian), but not on the type of ownership of an outlet (this factor rather influenced the number of publications and their exclusiveness). The Russian language media under consideration used the term “militiamen” (38,2%), and a little less frequent “terrorists” (24,7%).

The Belarusian language media, same as English language and Ukrainian language media, used “terrorists” in the first place (72,1%) and “gunmen” («баевікі» (20,9%)).

Thus, to refer to illegal armed groups in the Crimea and in the South-East of Ukraine, Belarusian journalists borrowed part of names from their Russian colleagues, and another part – from Ukrainian colleagues. Alongside with the names, a complex of stereotypes was also imported.

.PNG)

.PNG)

.PNG)

.PNG)